Shall We Gather at (the River) Our Churches?

By Ellen Blue

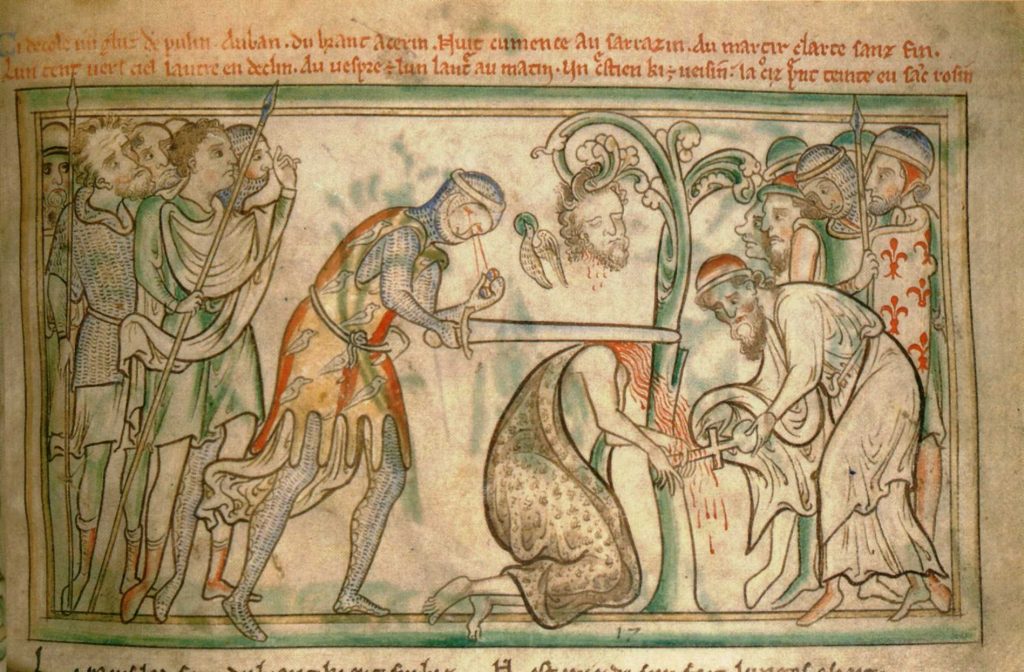

In the early days of the church, when Christians were being persecuted and even martyred, there was great excitement about dying for the faith. There are stories about believers who refused to be rescued from martyrdom even when they could have avoided it. There are tales of people who, on witnessing the executions of others, ran forward identifying themselves as Christians and demanding that they be killed, too. Church leaders eventually had to declare that so-called “voluntary martyrdom” did not count as true martyrdom in order to stop the trend.

At times throughout the past two millennia, totalitarian governments have made Christian worship illegal. Sometimes Catholic worship or worship conducted by certain Protestant denominations has been banned. Those who worshipped in secret to preserve a Christian presence in an area are deemed heroic. They did not deliberately court imprisonment or death by gathering publicly, but we still consider them faithful witnesses.

What does this history say to us in 2020 as various governors re-open their states during a pandemic and allow regular public worship to resume? What if a pastor insists that Christians must attend public worship in order to demonstrate their faith? Must believers convince themselves that Jesus will protect them from COVID-19 despite the warnings from medical professionals?

These questions are especially appropriate because we have opportunities to stay connected with our churches and other members in ways that congregations have not historically had. Zoom gatherings, email, social media, and webcasts of church services can let us stay connected. For those without internet, making telephone calls, writing notes, and watching televised worship can offer meaningful community.

We must also face the hard truth that if we attend public worship, it’s not just our own lives we’re risking. If I am exposed by a carrier without symptoms, then my family and everyone else that my family or I encounter may be exposed. As a United Methodist, I treasure our emphasis on connection, but at this moment, that connection is also a source of peril for the whole community.

The fact that the secular government gives churches the “all clear” to gather does not mean that gathering is the right thing to do. Plenty of things which are legal are not moral or ethical or Christian courses of action. I believe that staying home and avoiding the high risk of being infected at a service (and then inevitability exposing others) is precisely the Christian response to the pandemic. Both Christian tradition and the mandate of Jesus to heal, rather than harm, make it so.