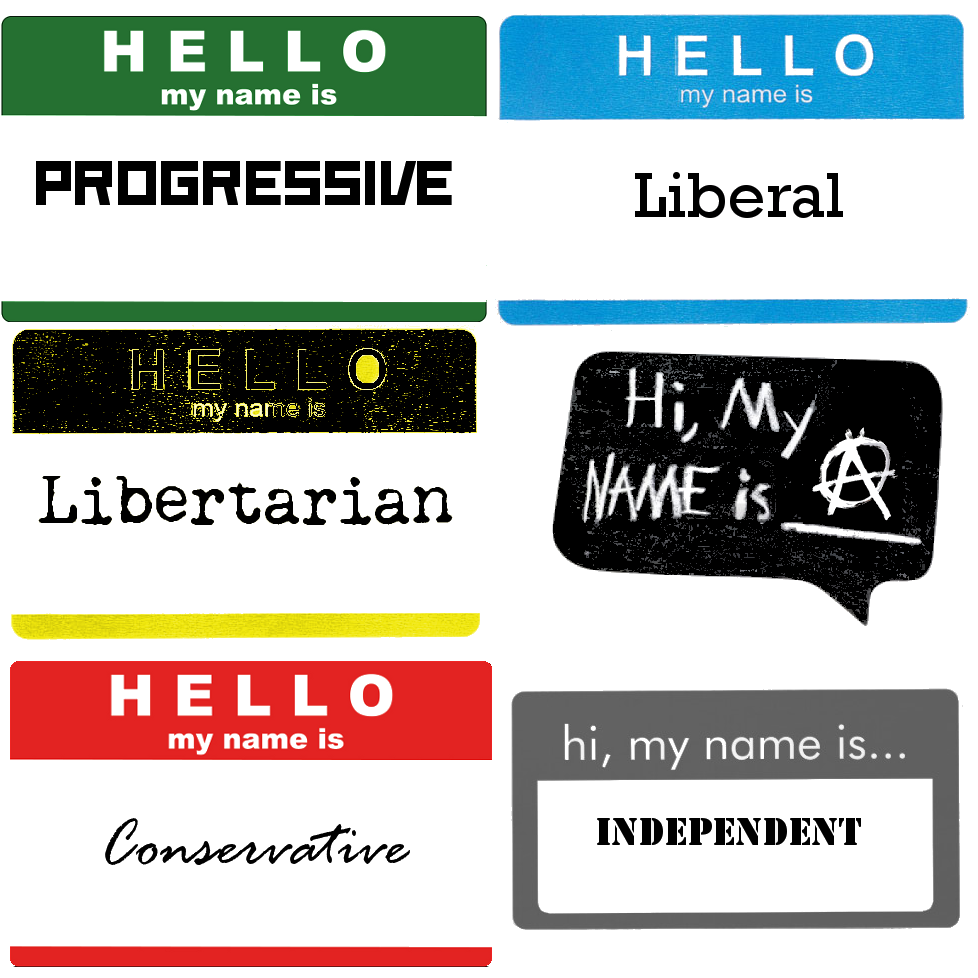

Label Bubbles

Political partisanship rules all types of discourse, including religious discourse. The terms that express political partisanship—alt-right, right, conservative, moderate, liberal, progressive, radical—have infected the nation’s speech.

Political partisanship rules all types of discourse, including religious discourse. The terms that express political partisanship—alt-right, right, conservative, moderate, liberal, progressive, radical—have infected the nation’s speech.

It is nearly impossible for religious types, who have been labeling ourselves and others for centuries, to eschew labels. But, today, labeling is dominated by partisan politics. And this partisanship occludes rather than illuminates, shuts down rather than opens, conversation and debate.

For several years during the beginning of my term as seminary president (2009-2018), I was very hesitant to use the term “progressive” to speak about the seminary’s orientation. I liked (and like) Dr. Hal Taussig’s essay on the real differences between liberal and progressive Christianity (progressive is not simply a substitute for the controlled-by-the-Right “L” label). But the word “progressive” in politics had a long and varied meaning.

Today, progressive in politics often paints liberals as pragmatic sell-outs to capitalism (think Bill Clinton and, for some, Barack Obama) whose solutions to problems are too incremental, based on compromises that feel like losses, and not sufficiently attentive to or disruptive of structural inequalities. While I came to accept a “progressive” label, it was because that term had the highest affinity with what I think Phillips is doing. But while one can’t write or interact in the religious or the political realms without labels, it is best to hold the labels very loosely.

I am not debating the merits of any of these political positions here. But using labels such as conservative, liberal, or progressive in a religion—let’s take Christianity in the U.S.—hides at least as much as they reveal.

For example, there are affinities between kinds of religion and kinds of politics, but affinities are not the same as identities. One can be conservative/traditionalist in religion and disengaged from politics (the Amish). One can be religiously conservative and staunchly justice-oriented on the behalf of the racial and economic justice in terms of politics (like Shane Claiborne, Nadia Bolz-Weber, Jim Wallis, William Barber, hosts of Catholic women religious, and Martin Luther King, Jr.).

Obviously, there are thought leaders where conservative religion aligns closely, even if at times weirdly, with conservative politics in persons such as Franklin Graham, Jerry Falwell, and Tony Perkins.

From a religious point of view, the above-named persons would be considered religiously conservative. But there is a canyon between Graham and Claiborne, for example, in terms of politics.

The terms liberal, conservative, and progressive mean increasingly little to me (and President Trump’s dominance in the Republican Party has shredded what conservative used to mean for Republicans). They are terms we use in public life to label ourselves or categorize others. We use the terms as substitutes for getting to know a person’s point of view, or to decide in advance who is trustworthy, or to put someone in a test tube to see what color the litmus paper turns.

In politics, rather than labeling, I prefer to ask questions such as:

- What are the roles of government, families, legislative politics, corporations, private foundations, non-profits, and voluntary organizations in creating vibrant public spaces and preserving privacy? In the dynamic interplay of public and the private spheres, where are the boundaries of expectation and responsibility?

- In addition to protecting people from foreign and domestic threats and enforcing contracts, what do you see as the purpose of government?

- What are the virtues we in the U.S. want to practice in relating to each other?

- Do you think democracy means “majority rules” or do you think democracy requires the protection by the majority of the rights of political minorities—or do you not care about democracy at all?

- Tell me what you think is right and what you think is wrong in the U.S. How do we get more of what is right and decrease what is wrong?

- When you say “family,” what do you mean? How should the sectors of society work together to support families?

- What should be the purpose of incarceration?

- In debating about taxes and the size of government, do you argue about big government versus small government, or do you advocate for government being as big as is necessary to get a particular job done effectively?

- What is the best way for our society to maximize citizens’ capacity to be responsible individuals?

- What is the role of the government in regulating corporations for the sake of public safety?

- How do you see the roles of the press, non-profits, religious organizations, and lobbying groups in holding elected officials accountable?

- Should there be a social safety net and, if so, which categories of persons should be included?

- What is the role of government, if any, in rectifying social inequities and promoting and protecting equity of opportunity, as well as in assessing outcomes?

- Which rights do you claim (such as free speech, free exercise of religion) that you have a difficult time extending fully to others?

In religion, rather than labeling, I would rather ask questions such as:

- Do you think it is important to be a discerning and generous person in all ways—the way you listen, the way you give, the way you forgive?

- Where do the practices of confession, penance, and forgiveness fit in your faith, and if you seek to practice them, how are you doing that?

- Would you say you trust in God? What do you think that phrase means? What are the practical consequences of your belief?

- What is your understanding of sin, and what difference does that understanding make in how you reflect about your own motives and interpret the motives of others?

- According to your interpretation of your faith tradition’s core narrative, what time is it for the world? What time is it for the U.S.?

- Which religious practices or expressions have you seen that would you rather the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment not include?

- In what ways do your so-called conservative, liberal, or progressive religious beliefs and values clash with conservative, liberal, or progressive points of view in politics? (In my opinion, if the answer is “Umm. I don’t see any clash”, there may be a problem worth investigating.)

- Is the teaching of your scriptures self-evident to the rightly informed, or do scriptures need to be interpreted in the context of communities of interpreters?

- How would you define what it means to be a well-educated person, and how is such education best accomplished?

- Do you want the government to exclude everything religious, make space for religious communities to bring their value-systems into public spaces, or reserve center-stage for a particular religion?

- Is Christianity primarily a John 3:16 salvation religion to prepare adherents for life after death, primarily a Matthew 25 religion that concerns how Christians treat “the least of these” in this life, primarily a wisdom tradition regarding how to love God, self, others, and the garden (the earth), or what?

The problem with asking such questions is that categories will blur, boundaries will swiss-cheese and move, and we would not be able to argue with the self-righteousness that destroys relationships like acid rain killed lakes in the Northeast.

The joy I imagine in asking such questions is in the conversations and arguments that would ensue—as long as we stay present with the persons and the questions rather than retreat into our label bubbles.

Comments are closed.