Mr. Smith’s Washington, without Destructive Religion

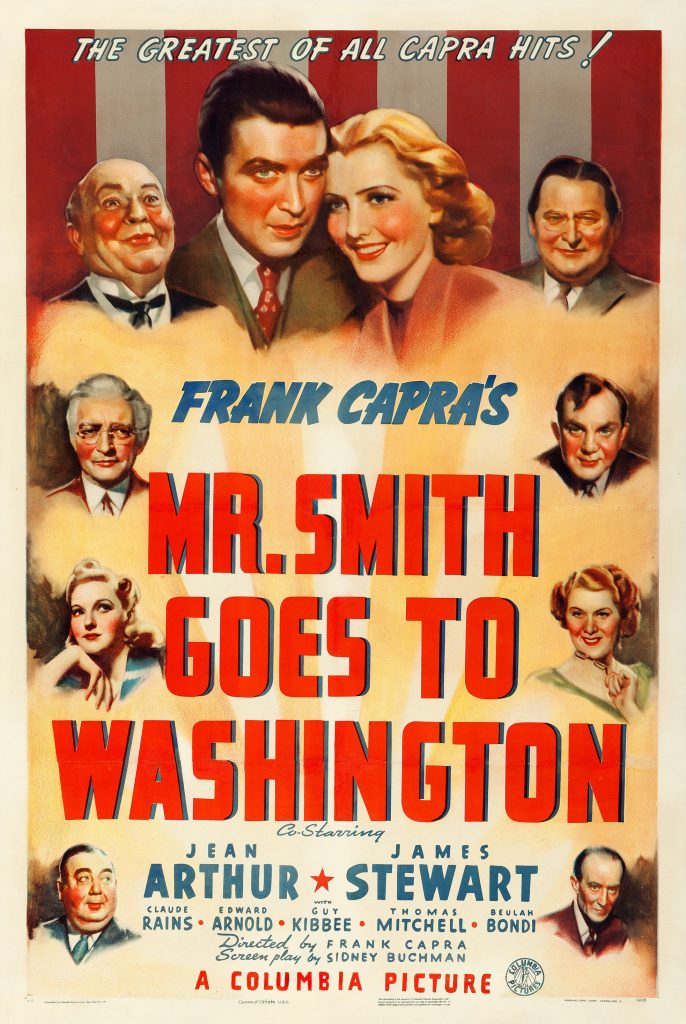

Last week, I took an afternoon to watch Frank Capra’s classic film, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. It was a treat! What I saw in this 1939 film was both familiar and foreign, and the absence of religion from the film was among the most striking differences.

To recap the film (I’d say “spoiler alert,” but again, the film was released in 1939): in an unnamed state somewhere in fly-over country, the U.S. senator dies and the governor must name a replacement. The near-mafia boss, big-money kingpin wants the governor to name the replacement. But what Boss Jim Taylor most desired was someone who could be manipulated to serve Taylor’s interests.

To recap the film (I’d say “spoiler alert,” but again, the film was released in 1939): in an unnamed state somewhere in fly-over country, the U.S. senator dies and the governor must name a replacement. The near-mafia boss, big-money kingpin wants the governor to name the replacement. But what Boss Jim Taylor most desired was someone who could be manipulated to serve Taylor’s interests.

The governor’s kids suggest he appoint a really swell guy, Jefferson Smith. The kids all know Smith because Jeff Smith runs a wholesome boy’s organization called Boy Rangers. The governor discovers that Smith’s father and the senior senator, Joseph Paine, were best friends. Paine was already in the governor’s pocket and in-step with whatever corrupt money-making project Boss Taylor desired. The governor decides to appoint Smith, who was without guile and who—it was assumed—could be easily manipulated.

Jeff Smith, played by Jimmy Stewart, is principled, decent, naive, awkward around pretty women, and totally in love with his image of America and of Washington. In his imagination, this is a nation of high ideals, and Washington should be full of them. He admires Senator Paine because he and his dad fought lost causes together, on principle. Smith assumes both Paine and Washington are worthy of his admiration. The viewer soon learns Smith will be subjected to a very rude awakening.

His new colleagues make sport of the rube from the plains. The press is particularly mean-spirited. His assistant, Clarissa Saunders, is jaded and can’t fathom how a decent man even belongs in Washington. That said, Saunders soon comes to admire Jeff’s pure spirit. She mentors him. Her mentorship provides a critical infusion of savvy knowledge regarding how Washington works. Those lessons are vital when Smith introduces a bill to fund a national boy’s camp in his state on land that happens to be targeted by Boss Taylor, in cahoots with the governor and Senator Paine, for a corrupt business deal.

Paine leans first gently and then hard on Smith to fall into line with the business deal, which Smith immediately recognizes as corrupt. Smith stands on principle and refuses. Paine accuses Smith on the senate floor of bilking boys of the pennies he is soliciting for the camp because, he claims, Smith is the one trying to make money off the land. At a low point, Smith returns to his favorite monument, the Lincoln Memorial, which both be and the others who enter there treat as sacred ground. From Saunders, he learns he can filibuster the land funding bill and try to demonstrate the truth of his claims. Meanwhile, Saunders and a reporter friend scheme to blanket the media in Smith’s home state in hope that maybe, just maybe, they can turn public opinion against the Boss, the sitting governor, and the revered senior senator. What could go wrong?

The Boss demonstrates why he is the boss, shutting down news of Smith’s allegations and of his righteous filibuster throughout the state. The Boy Rangers, however, believe in Smith and mount their own news campaign, which the Boss violently suppresses, even injuring some of the boys. But back in Washington, toward the end of what became a 25-hour filibuster, some senate colleagues began to admire Smith’s idealism. Some were moved by his speech, including the senator presiding over the proceedings. Then, in the dramatic concluding scene, Smith collapses from exhaustion (but will be okay). Paine, overwhelmed with guilt, runs from the senate chamber and tried (unsuccessfully) to shoot himself. Paine returns to the chamber and confesses on the senate floor that he’d been lying and everything Smith said was true. Saunders is thrilled, a cynical reporters has seen a good and honest man in Washington, and the presiding senator smiles.

What struck me as similar to our day:

- Cynicism in Washington and about Washington.

- The battle between wealthy people trying to manipulate the system to serve themselves and, on the other side, a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people which shall not perish” but is always in danger of perishing.

- The public’s perception of a press corps more interested in a juicy story, or ruining a career, than in truth.

- The willingness of adults to be violent against those who block their interests, including against children.

- The media image that the middle of the country is unsophisticated as compared to the East Coast.

What struck me as different from our day:

- Senators changing their minds.

- There was hardly talk about Democrats and Republicans. Our current party divide was not a meaningful division in the movie.

- Black people are cast in the movie as porters. There is one Black man who pauses at the Lincoln memorial, and one Black child among the Boy Rangers cub reporters. Otherwise, race is not mentioned.

- The portrayal of any adult in the U.S. being as idealistic about the U.S. as Jefferson Smith.

- The complete absence of traditional religion from the storyline.

In a blog of musings about religion in public life, it is, of course, this last point that led me to write this entry. I heard someone say that history, for most of us, is no longer than one’s own lifespan. One of the chief values of learning history is that we learn so many things we assume to be “the way things are and always have been” are, in fact, relatively new developments. For example, the time between World War I and World War II was a time of religious depression in the U.S. Interest in religion was down. In the post-World War II era, organized religion surged due in no small part to the suburban building boom and strong opposition to “godless communism.” Those days were also marked by spring-like ecumenical cooperation and sharing rather than polarization.

The religious, and political, polarization of today is rooted in narratives that diverged from the civil rights movement on, intensified by differing responses to race, gendered relations and sexuality, war, the value of equality, and whether peace is the absence of social conflict achieved through law and order or a result of just relationships. This polarization manifested in and was amplified by Newt Gingrich’s disdain for compromise and transformation of opponents into enemies. And, in religion, from the 1980s onward, historians can document the move to take religious wars of children of light v. children of darkness from the realm of denominational battles into the political sphere. Resist federal intervention into states, especially regarding how discrimination is defined. Elect Christians. Demonize secularists and the wrong kind of Christian. Continue to rail against godless socialism and to support free enterprise as God’s will. Denominate the president as God’s chosen.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was a tribute to the best angels of America’s nature: the possibility of a self-governing people, taking responsibility for themselves and each other, dedicated to both liberty and equality, where politics is pursued to better everyone, and where religious leaders neither volunteer nor are drawn into a war against these angels.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

IMAGE CREDIT: By Illustrator unknown; work-for-hire on behalf of Columbia Pictures. – Scan via Heritage Auctions. Cropped from the original image., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=85717591

Comments are closed.