Question Not the Beliefs but the Therefores

The Constitution protects the freedom of religious believing. Citizens should be tolerant of other’s beliefs. The government cannot be used as a tool for heresy hunting or for burning an alleged heretic at the stake—figuratively or literally.

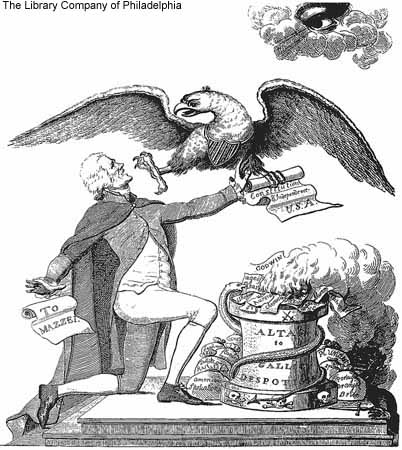

Yes, there have been seasons in our history where there was deep suspicion of Catholic candidates for office, with President Kennedy being the most famous case. Many religious leaders thought Thomas Jefferson, who did not pass an orthodoxy sniff test for any Christian faction, was an infidel. As remembered in an article last week, William Howard Taft’s religious beliefs, whatever they were, came under attack for his alleged Unitarianism. And despite the prohibition in Article VI of the Constitution of there being a religious test for holding office, many Americans continue to get queasy stomachs when considering an atheist for office, starting with the suspicion of one who does not believe in God.

Yes, there have been seasons in our history where there was deep suspicion of Catholic candidates for office, with President Kennedy being the most famous case. Many religious leaders thought Thomas Jefferson, who did not pass an orthodoxy sniff test for any Christian faction, was an infidel. As remembered in an article last week, William Howard Taft’s religious beliefs, whatever they were, came under attack for his alleged Unitarianism. And despite the prohibition in Article VI of the Constitution of there being a religious test for holding office, many Americans continue to get queasy stomachs when considering an atheist for office, starting with the suspicion of one who does not believe in God.

This matter of what a candidate believes is alive in public once again regarding both a presidential candidate and a Supreme Court nominee. In this case, both persons are practicing Catholics.

Their beliefs, how “alive the dogma” is in them, cannot be matters on which elections or confirmations depend. Whether or not one professes to adhere to a particular religion, whether one can be embraced as “orthodox” on matters such as the virgin birth, substitutionary atonement, how conservative or liberal one is on doctrinal matters, or how one reads and interprets a text must not be doors or walls to holding office.

However, religious practices and religiously-motivated practices—those are a different matter. The Constitution does not protect all religiously-motivated actions, no matter how “sincere” the action is. And neither should candidates for public offices be shielded from answering questions about how their beliefs, religious and otherwise, might translate into actions.

On the one hand, we should all be careful to understand before drawing conclusions. A judge can believe abortion is wrong and uphold a law which permits abortion. A candidate for office who is not religious can be entirely respectful of religious rights and of the value of religion in regard to promoting works of justice, charity, and mercy. And, it is also possible that a judge searches case for precedents that might nullify a present law, or atheist candidates could be anti-religious bigots who do to religious people what they felt they have done to them.

On the other hand, we and our representatives in elected offices are entirely correct to explore the “therefores” of beliefs, religious or otherwise.

Therefores matter.

For example:

A candidate for an environmental watchdog post who believes that Jesus is coming any day now should be questioned on how that belief might inform the candidate’s determination for protecting the planet for the sake of future generations.

Any candidate who has somewhere written that monarchy is preferable to a democratic republic because one can’t find democracy in the scriptures but kings are everywhere should be questioned bluntly regarding how they can possible hold an office at any level of government in the U.S.

A candidate teaches a class in his congregation’s religious school. In that class, the candidate teaches that men should rule as the leaders of households and public spaces, with women subservient to them. The man shows his students where in the scriptures this teaching is found. That candidate should be questioned in public, not on his interpretation of the texts (that is for adherents of that religion to debate) but on how he could work with female colleagues as equals.

To cite one real life example from the angle not of candidacy but from what someone does with a religious belief in a public office: when Jeff Sessions was the attorney general of the U.S., he was wrong to cite Romans 13, about submitting to the governing authorities. Wrong to cite this text at all, in public, for he offered that text as public justification and legitimization of his actions. The attorney general of the U.S. cannot take his belief in the validity of his religion’s text, insert a “therefore,” and declare a policy.

The moral order—the sense of and warrants for right and wrong, good and bad, of what people in the society owe to each other—in a diverse, complex society is not determined by one set of beliefs, one orthodoxy, forming one intellectual highway, moving to a common destination. Rather, there may be many different belief-paths that lead to the same policy outcome; and persons who believe in very similar ways may split when it comes to the “therefore” of their beliefs.

Certainly, questioning what a candidate or nominee believes about God or the afterlife, and whether a ritual is symbolic or effects a change in the participants, is not a legitimate line of questioning in confirmation hearings or an election debate. But asking about the “therefore” of beliefs, about how a belief might affect decisions vital to the candidate’s potential office—that is absolutely legitimate and necessary.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

IMAGE CREDIT: The Providential Detection. Etching by an unknown artist, c. 1800. The Library Company of Philadelphia (159)

Comments are closed.