Mind the Virtue Gap

These attributes distinguish a democracy from a mob—at least according to the American defenders of democracy around the time of the nation’s founding:

- Respect demonstrated by the majority for the rights of political minorities

- A well-informed, virtuous public.

Now, as is evident in today’s “we live in separate universes of facts and meaning” polarization, the rights of political minorities and a “well-informed public” are both deficient. For example, Oklahoma’s legislature is completely dominated by one party which needs and engages the opposing party for, basically, nothing. And, surveys indicate an astonishing percentage of the U.S. public, especially in the party that lost the election, continues to believe their candidate won more votes than the actual winning candidate.

But for today, I will focus on the other deficiency: a virtuous public.

What “virtuous” means is, of course, contested, as one would expect in a democracy! However, walk with me a moment.

Virtuous refers to public virtues, the kinds of character strengths and moral commitments in citizens a nation needs in order to maximize self-governance.

What if we distilled virtues into just this one: personal responsibility? That may be the virtue which elevates moral agency to the level necessary to become a well-functioning democracy.

How is personal responsibility expressed? Personal responsibility is manifested—or its absence is evident—in work, in relationships, in what one does when one makes a mistake, and in the depth of a commitment to mutuality.

Does a person work, whether in the for-pay economy or raising children or volunteering, to the best of their abilities, to make a positive difference in society? Does one participate in personal and social relationships in healthy ways? Does one acknowledge mistakes and seek to rectify errors and damage? Does one acknowledge and act upon the insight that one’s own freedom is bound up in, and also constrained by, the freedom of others?

I imagine most people on both sides of conservative-liberal debates would affirm the virtue of personal responsibility and the four ways through which taking responsibility is expressed.

If, as the U.S. Supreme Court in Citizens United wrote, corporations are “persons,” then apply the virtue of personal responsibility to corporate persons, too.

Now, in your judgment, what is the gap between being a virtuous public and the one we are now? My take is: the gap is large, for both individuals and corporations.

And the places to learn the virtue of personal responsibility and its attendant expressions are few. And growing fewer. The urgency of addressing this virtue gap is accelerating while the places for moral education are either diminishing or highly contested.

Consider that maximizing the morality of personal responsibility is difficult in a relatively homogeneous society, where individuals recognize each other as “same.” How much the more is it challenging to recognize others as kin in:

- A nation of nations, and of states which sometimes would rather be untied than united.

- A collectivity of peoples of many, many different local and regional cultures.

- Our long history and present practices of creating racial hierarchies and tolerating economic inequities.

- A time when no unifying national narrative rings true.

Many societies utilized religion as a unifying force and a teacher and guardian of social virtue. With more than 250 recognized expressions of religion in the U.S., and with the barriers to an established religion in the Constitution, the whole category of religion is more of a gladiator game than it is social glue or moral academy.

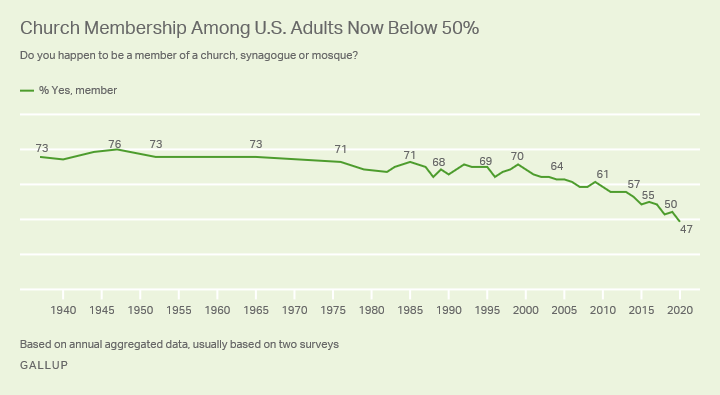

Moreover, a very recent Gallup poll finds that less than 50 percent of the American public is affiliated with any religious congregation. And the downward trend continues. This means religions will be less and less important as sources for morality, person and public.

Moreover, a very recent Gallup poll finds that less than 50 percent of the American public is affiliated with any religious congregation. And the downward trend continues. This means religions will be less and less important as sources for morality, person and public.

So, it is no mystery that, in the absence of a religious glue and of a dominant religion functioning as teacher and guardian of public virtue, we see:

- Some Christians claiming Christianity as the nation’s true identity and doing everything in their power, including through legislatures and courts, to defend against what they see as the ungodly onslaught of secularism and liberalism.

- Presidents using executive orders to steer public virtues in one direction or another.

- Federal court rulings, increasingly from judges appointed by the Bush and Trump administrations, functioning as moral adjudicators.

- State legislatures spending their time and attention on flash-point social issues and comparatively less floor time on matters such as the budget and all the programs a budget serves.

In other words, these are attempts to serve as social glue and public morality; and we should all be worried about the results.

These attempts at shaping, and sometimes coercing, public virtue are played out in public schools. Among all the other huge challenges facing public education in the U.S., let’s add the polarized public morality contests of adults who can’t see their way past the win-lose scenarios they/we created.

The U.S. has become an incredibly complex, multi-everything society. By the mid-2040s, there will be no racial-ethnic majority. We are a society that, in terms of human brain development, is extremely challenging. Human beings are wired to be more wary of strangers than of “like us.” This fact, along with the absence of transcending religious commitments or true-ringing national narratives, make a virtuous public, filled with and led by individuals and corporate persons who exercise exemplary personal responsibility, maximally difficult. If religious affiliation continues on its downward course, religion will be a weaker influencer of public morality than it is now. I don’t know anyone who sees the polarization evident in presidential elections, court decisions, and state legislatures diminishing soon.

Are there current or potential schools of public virtue that are or could be, up to the task for the challenges we face? I am sure there are legions of examples and experiments. Consider the social justice actions taken and inspired by Black Lives Matter, Stoneman Douglas students who survived mass murder, Moral Mondays, and Greta Thunberg. But I think we need a movement on the scale and energy of a revival. Scale and energy, yes, but we do not need a return to “old time religion” or any past era. We need something we’ve not yet seen for the nation we’ve not yet been.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Leave a Reply